At the beginning of October, the Norwegian Nobel Committee, chaired by Berit Reiss-Andersen, awarded this year's most prestigious prize (in the view of this Foundation of course), dedicated to Peace, to Iranian activist Narges Mohammadi, for her fight "against the oppression of women in Iran and her fight to promote human rights and freedom for all", a mission that the winner has pursued with courage and determination for practically all of her life.

51 years old, engineer by profession, and writer and journalist by vocation, Ms. Mohammadi is currently serving a 10-year prison sentence in the notorious Erin prison, having been found guilty of 'spreading anti-state propaganda’ by an Islamic court. For the dauntless activist, today's imprisonment is neither new nor an isolated event, considering the fact that it was preceded by no less than thirteen arrests and four convictions, not to mention instances of corporal punishment (the sadly infamous floggings).

Surprising as it may be, the fact that the Nobel Peace Prize has been awarded to an Iranian is not unprecedented.

Exactly 20 years ago, it had been awarded to Shirin Ebadi, lawyer and founder in Tehran of the Centre for the Defence of Rights, a non-governmental association in which the new Nobel Prize laureate had also had the opportunity, so to speak, to 'cut her teeth', working side by side with the person in charge.

That the Prize be awarded 20 years later in what is essentially a “photocopy” of Shirin Ebadi’s situation causes us to make two opposing considerations.

The first, undoubtedly positive one, reflects on the award as confirmation of the profound social commitment and admirable degree of personal self-sacrifice that Iranian women devote to affirming levels of emancipation more in keeping with their 'gender' dignity, despite being fully aware of the risks this entails. Those granted by the theocratic regime installed with the 1979 revolution are, in fact, of little more than symbolic value. These qualities were also very evident last year during the impressive demonstrations called by the 'Woman, Life and Liberty' movement (see issue no. 27 of 'Voce' dated November 2022), in the wake of the dramatic beating (with unfortunately lethal consequences) of the young Kurdish woman Mahsa Amini, guilty of not having worn the Islamic veil (hijab) 'correctly'.

The second, which leaves a decidedly negative mark, is the objective testimony to the protracted, invasive entrenchment in every compartment of Iranian society of an implacable system of public control (in which the religious component plays a central role), leaving little or nothing to the free choice of individuals, least of all women. The brutal assault suffered a few weeks ago by the teenager Armita Garawand, who was beaten to death by the 'moral police' for a similar offence to that committed by Mahsa Amini, is, once again, proof of this.

At the time, the massive mobilisation among the Iranian population, coupled with the extensive international awareness campaigns promoted on five continents, had led us, like other commentators, to trust in a gradual erosion of the capillary power hitherto wielded by the ayatollahs and their acolytes.

Exactly one year on, it is with deep disappointment that we have to recognise that these hopes have not been fulfilled and that, if there has been any change, it has, if anything, resulted in a further radicalisation of the deadly system of prohibitions and bans currently in force.

This involution has certainly been influenced by the continuation of the Russian/Ukrainian conflict with no apparent solution on the horizon, with increasingly alarming consequences for future geo-strategic arrangements, not only in Europe but also worldwide. As was widely foreseeable, the severity of that crisis has had the effect of drawing the primary attention of virtually all governments, the corresponding public opinion, and the information networks to that geographic area, diverting them from other, albeit far from secondary, latitudes.

And we must also acknowledge, with similar regret, that in recent times, frankly disconcerting signals have been received precisely from the international community. How, for example, should we judge the decision by which the UN even entrusted the presidency of the influential Human Rights Council to one of the ayatollahs’ representatives? Although cloaked in noble motives, even the White House's deliberation to lift its freezing measures, and hand over the hefty sum of $6 billion to the Iranian regime in exchange for the release of some prisoners with dual passports, was not particularly brilliant, both in terms of expediency and timing of adoption. Despite the ritual denials of those directly involved, it is not difficult to imagine that a large part of those funds could be used by the authorities in Tehran not for the humanitarian purposes for which they are intended, but to increase the personnel and equipment of the 'guardians of the revolution' and to acquire new instruments of repression. If the US Government were to realise, albeit belatedly, this manipulation, it would undoubtedly now be inclined to reconsider this decision.

On the other hand, the demonstrations of jubilation with which the Iranian government and the radical sectors of the country that support it welcomed the criminal attack launched against the territory of Israel at dawn on 7 October, the feast of Shabbat, by Hamas terrorists is significant of the irrelevance, for the theocratic regime, of the need to preserve even a semblance of dialogue with the West. The terrorists, who receive from Tehran not only the main sources of funding but also armaments and cynical political endorsement, staged an attack that cost the lives of hundreds of innocent victims. Against this backdrop, the ill-considered decision of the current Brics members (see the October 2023 issue of 'Voce') to invite Iran to join that important group of states, thus connoting it with a, probably irreversible, fundamental anti-European and anti-American stance, is also cause for concern.

In conclusion, returning to the prestigious award bestowed on Ms. Mohammadi by the Nobel Prize Committee, the immediate comments made by UN Secretary General António Guterres ("this is a reminder that women's rights are being harshly repressed, in Iran and elsewhere") and Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi ("this is a partisan political move against our country, which we strongly condemn") bring out its obvious, complete irreconcilability. On closer inspection, the same comments help to further reinforce those walls, both physical and cultural (called divar in Farsi), which the new laureate has always worked selflessly to stubbornly oppose.

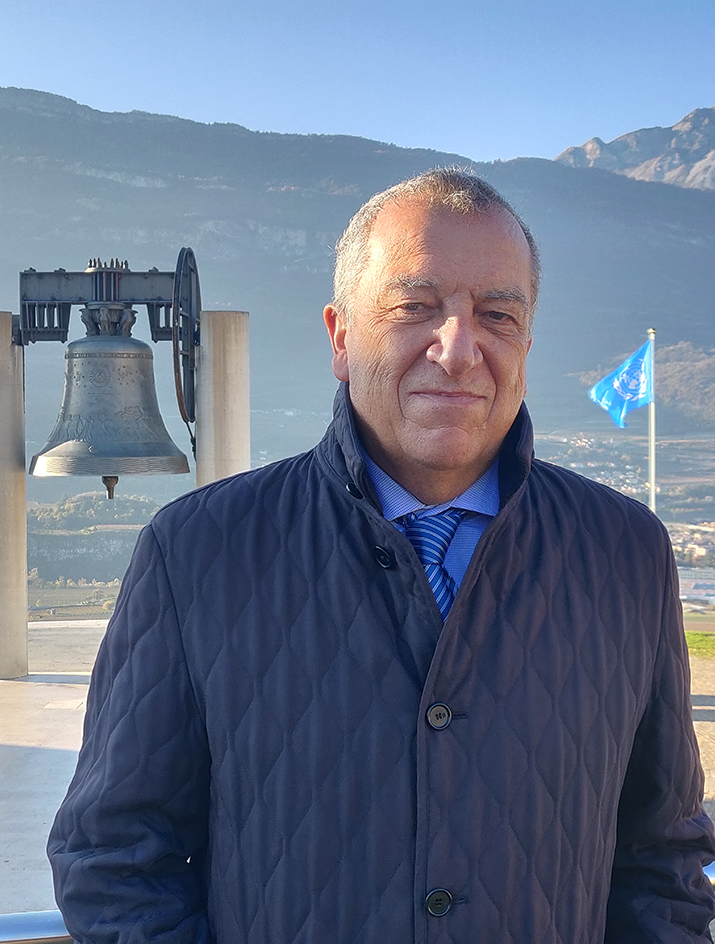

In its narrower context of competence, the Campana dei Caduti Foundation will continue to express its staunch solidarity with the Iranian opposition, active both at home and in exile, by flying the Iranian flag displayed, alongside 105 others, along its evocative 'Avenue of Nations’ indefinitely at half-mast, as a sign of mourning and condemnation.

Reggente Marco Marsilli, Foundation President