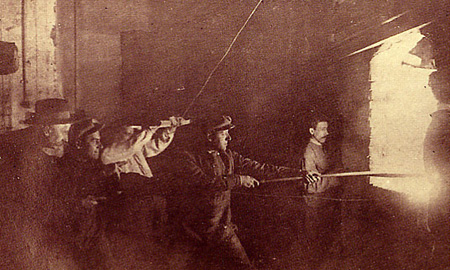

The Bell was finally cast in Trento on 30 October 1924 at the foundary of Luigi Colbacchini in Dos Trento. The casting was attended by several “godmothers” or female sponsors and the Prince-Bishop of Trento, Monsignor Celestino Endici, as well as a select group of civic leaders and guests. At the moment of smelting, the sponsors threw gold donated by the women of Italy into the boiling bronze. In the courtyard of the foundry two enormous furnaces were blazing, consuming huge piles of firewood, while between the two, buried some three metres deep in the ground was the plaster and wax mould for the Bell, made by Zuech, with a "mouth" in its centre to receive the molten bronze. The ceremony began at 10:30 am. The elderly smelter gave his strict orders: this was an important occasion, and everyone was nervous. But suddenly, one of the furnaces began to crack, and metal started running out. At the cry of "In the name of God", the taps in the furnaces were opened and the incandescent bronze began to flow into the mould of the Bell: it was the moment of casting. In his diary, Don Rossaro described the scene as follows: «The whole thing lasts 8 minutes. The cry of Viva Italia announces success. Bells ring. Cannons fire. Trento flies its flags - in many cases the Holy Rosary is said. The Canzone del Piave is sung in schools". From a figurative point of view, the Bell was an enormous success. Its streamlined, elegant shape came from the smelter, its decoration from Stefano Zuech. It weighed 11 tonnes and it was 2.58 metres high and 2.55 metres in diameter. Twelve people could fit inside. It was Italy's largest bell and one of the biggest in the world, exceeded only by the bells in the Moscow Kremlin, Cologne cathedral and the church of S. Stefano in Vienna. The clapper too was acclaimed as a masterpiece: donated by Brescia firm Franchi-Gregorini Metallurgia Italiana in remembrance of the city's fallen, it was hand-carved by Gaetano Ticci from Siena to a design by Egidio Dabbene. It was some 2 metres tall, weighed 400 kilos and was decorated with garlands of flowers and leaves, the base bearing the date 1925 in Roman numerals (MCMXXV).  In the following months, while the bronze cooled and prior to its solemn arrival in Rovereto, Don Rossaro - tireless builder of a modern-day legend - occupied himself with the creation of a poetic and spiritual aura around the Bell, thus endowing it with a substantial body of literature both large and small-scale and not without the somewhat rhetorical flavour of the day, influenced by the cult of those who gave their lives for the fatherland. In one of his early projects (initiated before the bell was cast), Don Rossaro sought to involve the highest echelons of the State, inviting all the generals and commanders who had taken part in the conflict to contribute a thought or a motto. Furthermore, he asked the Queen Mother Margherita, sponsor of the Bell, for a prayer, which she wrote in her own hand: "Lord, receive in Your light the heroic souls of those who have sacrificed one of Your greatest gifts, giving their lives for the honour and glory of our fatherland; and let the sound of this Bell join the prayers that rise up to You from this earth of martyrs and heroes, with those that come down from Heaven, into a single invocation to You, Lord, for the future and the greatness of Italy! June 1924, Margherita”.

In the following months, while the bronze cooled and prior to its solemn arrival in Rovereto, Don Rossaro - tireless builder of a modern-day legend - occupied himself with the creation of a poetic and spiritual aura around the Bell, thus endowing it with a substantial body of literature both large and small-scale and not without the somewhat rhetorical flavour of the day, influenced by the cult of those who gave their lives for the fatherland. In one of his early projects (initiated before the bell was cast), Don Rossaro sought to involve the highest echelons of the State, inviting all the generals and commanders who had taken part in the conflict to contribute a thought or a motto. Furthermore, he asked the Queen Mother Margherita, sponsor of the Bell, for a prayer, which she wrote in her own hand: "Lord, receive in Your light the heroic souls of those who have sacrificed one of Your greatest gifts, giving their lives for the honour and glory of our fatherland; and let the sound of this Bell join the prayers that rise up to You from this earth of martyrs and heroes, with those that come down from Heaven, into a single invocation to You, Lord, for the future and the greatness of Italy! June 1924, Margherita”.

Plans continued to flourish in the priest's mind, and next was his idea to invite Italian artists to send a parchment depicting a campanile or tower in their cities. Then in October 1922 came the idea of collecting the signatures of the 12,000 contributors in a "Golden Register of the Bell", which would attest to the debt of gratitude owed to all those who had helped the project. Three copies of this register were drafted: one was placed in a special niche in the first stone on the day of the Bell's inauguration, the second was placed in the Archive for consultation, and the third copy - on parchment - was donated to the Municipality for the Civic Library; the intention was to embellish this latter copy with a series of illuminated plates. To this end a call was launched for "willing artists" to send a parchment with a painting by them. The regulations sent to the artists included the following: "The subject to be undertaken will be the monumental Bell of the Fallen, celebrated by its sisters in Italy. Each parchment must therefore contain a similar image: a historic campanile, an ancient tower, an attractive dome, with bells festively pealing, adding their voices to that of their big sister. Every province has a tower or a bell celebrated in art or in history: so let us pay due homage to them and let them shine on the parchment that will adorn this exquisite volume". The priest's call was heeded, and from every corner of Italy came contributions by artists famous or otherwise, talented or not. The first parchment to arrive was from the city of Macerata in July 1924, an exquisitely illuminated work by Professor Elia Banci; this was soon followed by works from Benevento, Brescia, Perugia and many more. Alongside this idea was that of asking Italian women - the mothers, widows, orphans and wives of the fallen - to offer various gold items: earrings, brooches, rings, medals and other trinkets without artistic value, to be smelted along with the bronze of the cannons in order to improve the composition of the metal, and as a demonstration of their piety and love. This appeal was also rapidly answered, and in a short time Rovereto received an influx of countless gold items, often accompanied by particularly moving letters and notes. An anonymous woman wrote:

“"I send this ring so that as it melts, it may be purified and consecrated in the mystical flame of the Bell of Heroes”.”.

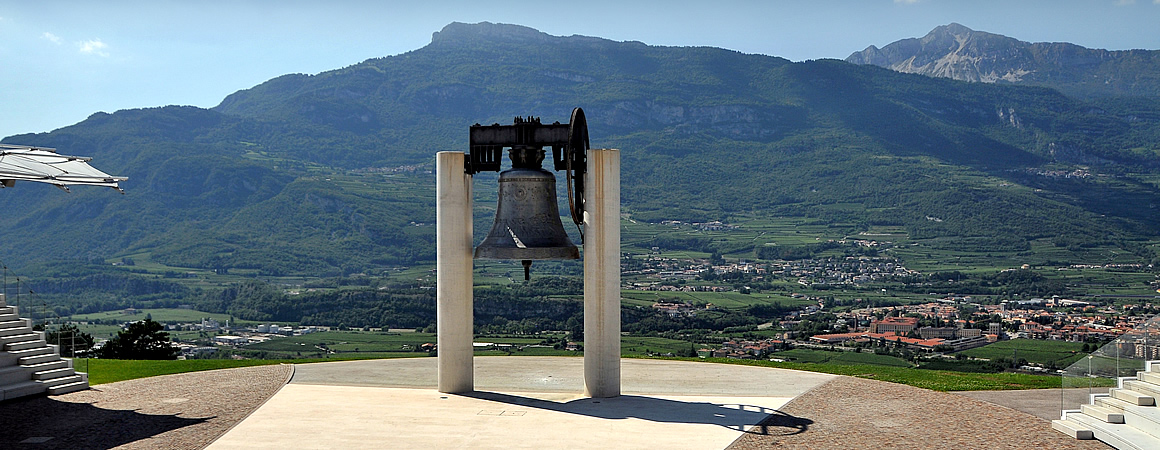

Another letter, accompanying a ring, read: "He gave it to me as he left for the battlefield, whence he will never return. Becoming a Bell, may it carry my kiss and my prayers to his faraway tomb every evening". Equally moving are the brief lines that arrived with a gold cross: "I was a smile in the cradle; I was sorrow at the grave; now I will be a song of peace and glory!" From Hungary came an anonymous letter containing a gold crucifix without words; and Don Rossaro did not have the courage to melt it, so he kept it carefully, wondering at the unknowable sorrow and hope carried within it. Some of the first offerings came from the widow of Cesare Battisti, the mother of the martyr Fabio Filzi and the widow of Nazario Sauro. Meanwhile, time was passing, and on 10 November 1924, architect Giovanni Tiella presented his design for the support of the Bell of the Fallen, consisting of a huge ring of concrete placed at the base of the Malipiero Bastion; on top of this there would be a structure of beams approximately 10-12 metres tall: the design was simple in architectural terms while at the same time austere, allowing the Bell to be seen from anywhere in the valley and giving free movement during its ringing.

For his part, in order to raise further funds, Don Rossaro commissioned the engraver Carlo Cainelli to produce an etching to be sold in limited edition; but sadly this was never completed, as the artist died unexpectedly on 8 February 1925.

A calendar of the Bell for the year 1925 was also prepared, architect Giovanni Tiella being charged with its graphic design and attractive cover. Thanks to Tiella's creativity and Don Rossaro's meticulous instructions, the official flag of the Bell, was also designed, to be raised as a standard on the castle flagpole. The flag was sky blue, with an elephant at the centre (symbol of magnificence and eternity) holding the Bell, flanked by a star and a golden crescent moon. The energetic priest even thought about a poem and an anthem for the Bell, for which he himself wrote the words. Don Rossaro had actually made a first draft of the poem in autumn 1922, as he returned by train from Vienna, where he had met the Austrian authorities to request cannons for smelting. Despite being a former irredentist, in the Austrian capital he nevertheless wished to pay homage at the tombs of the Habsburgs, in an "act of reconciliation with history". A national competition was launched in 1924 to write a score for the official anthem of the Bell; according to the call for entries, this should be "popular in nature, simple and clear in form and with a single part, also suitable to be sung while marching". A total of 97 entrants presented their works and when the panel of judges met on 29 February 1925, the winner was Maestro Ero Mariani from Milan (his anthem was performed for the first time on the occasion of the Bell's baptism).