MEASURING DEVELOPMENT

In 1990 the Pakistani economist Mahbub-ul-Haq, special consultant of the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) arrived at the definition of the Human Development Index (HDI). The intention was to «shift the focus of economic development from Gross Domestic Product to people-centred development policies». Previously, using the per capita GDP as a reference indicator, the attention of policymakers focused exclusively on the monetary value of the goods and services produced in a given territory in a year, i.e., on purely economic growth thereby losing sight of some essential elements for the well-being of man. In fact, per capita GDP has two main defects: first, given that the total value of the goods and services produced is divided by the population, it masks the unequal concentration of wealth in the hands of a few; second, it only measures growth in production, without considering capital (human and natural) that is lost in the process. If development is seen as the creation of an environment conducive to the full mobilization of everyone's potential, it becomes essential to broaden the horizon of research and measurements to other parameters. Economic growth alone does not guarantee human development intended as the satisfaction of essential needs, the expansion of opportunities or the freedom to make choices concerning one's life.

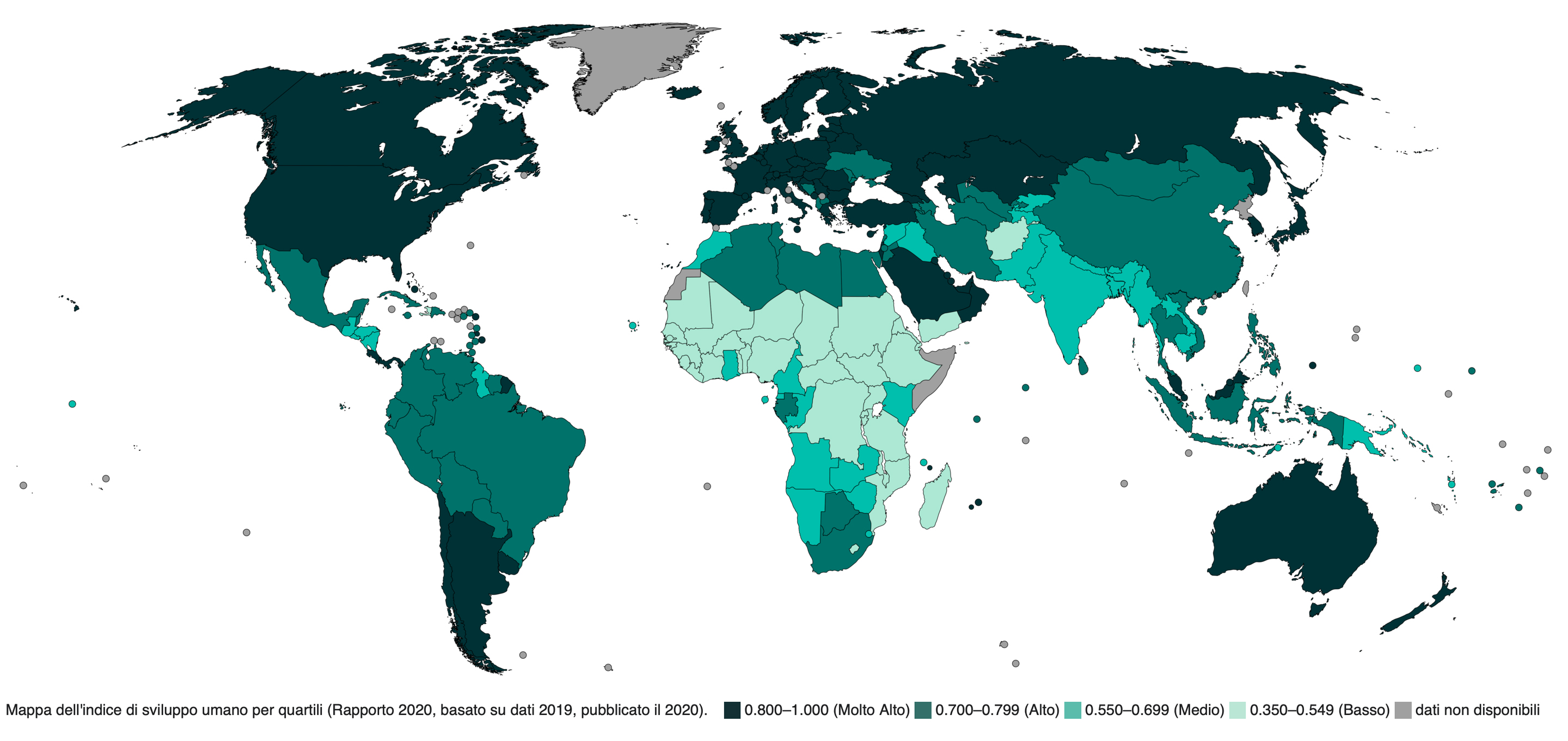

Immediately after its definition, the HDI was implemented by the UN as a measure of the quality of life in the various countries of the world. Since 1990, a «Report on human development» has been published by the UNDP in which 140 countries are classified into four groups with different levels of human development: very high, high, medium and low. In addition to the economic factor (represented by per capita GDP), the HDI combines indicators such as literacy and life expectancy at birth. The goal is to measure which countries are in a position to create an environment capable of providing a longer, healthier and more creative life.

Other indices have been introduced in the various reports that have appeared in the last three decades, the result of further elaborations and distinctions in the statistical data: the Human Poverty Index (Hpi) which describes the cases of deprivation of the three fundamental dimensions of the HDI (economy, education, health) such as the probability of exceeding a life expectancy of 40, the presence of functional illiteracy (inability to use reading, writing and calculation skills in daily life), the percentage of the population without water; long-term poverty and unemployment (for developed countries); the Gender Development Index (Gdi) which measures the results achieved in the same variables, but taking into account the inequalities between men and women; the Gender Empowerment Index (Gei), which evaluates and measures how much women are placed in a position to actively participate in economic and political life.

Over the years, the findings made regarding the HDI, especially those of a technical nature, have made it possible to improve the calculation methodologies. In particular, the HDI has been "accused" of not highlighting the inequalities existing between social classes or ethnic groups within the same country, of neglecting human rights, of not containing indicators relating to freedom and culture, of failing to consider the need for a valid ecological dimension. Precisely in response to this last criticism, an "environmental pressure" index was added in 2020 on an experimental basis.

Therefore, the political value of the HDI remains beyond any doubt, although it might sometimes run the risk of concealing rather than revealing. Also, for this reason its use by policymakers has progressively increased, as has the attention towards human development issues in general.

Andrea Fontemaggi