FOR WHOM THE BELL TOLLS - P14

On 2 November 1948, the tolling of the Bell was again broadcast on the radio. The aim was to speak to everyone, and say one thing: ‘Nothing is lost in Peace. All can be lost with war'. Pius XII's phrase was famous, but it might have been better to cast it on the bronze mantle of Maria Dolens so that it would remain an everlasting warning. It took a while. We had to wait until 1964, but eventually those words appeared right below the Ecce Homo, and they are still there today. Don Rossaro did not live to see them, but in his heart he probably knew that one day it would happen.

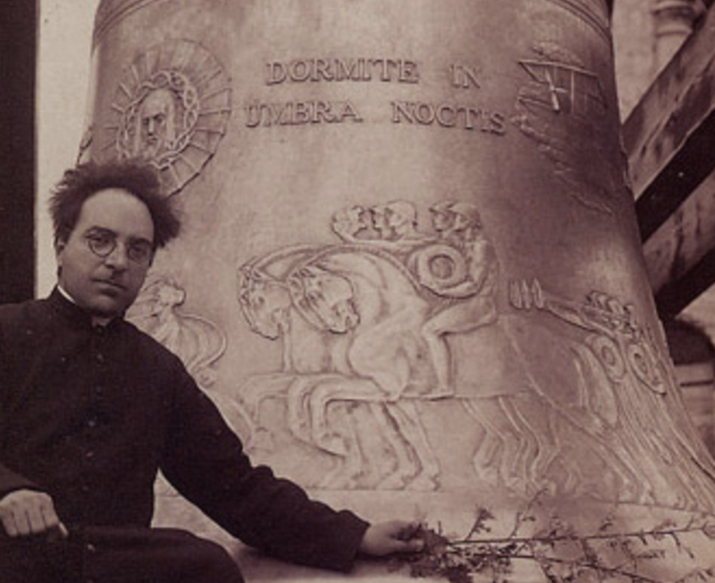

True, there were some practical problems, such as replacing the battlement that had broken, or widening the platform of the Malipiero bastion to allow more people to attend official ceremonies, but the thorniest issues were the ethical and moral ones. The most challenging endeavours of Don Rossaro were his attempts to preserve the original spirit of the Bell and enforce the statutes: Maria Dolens was only to sound in the evening and only to commemorate the victims, including civilians, of all conflicts.

Just as in the Fascist era, in the post-war period too, at every political or religious demonstration, someone would request the Bell to be rung at any given moment. This happened after the affirmation of the Republic on 2 June 1946, at the arrival of the Pilgrim Mother in 1948, and on many other occasions. Any "excuse" was used to request an exception to the rule, as if Maria Dolens had become a tool for celebrating events that, while undoubtedly important, were far removed from its true vocation. The priest from Rovereto continued to oppose it, each time emphasising the profound spiritual significance of the hundred chimes, which transcended the temporary circumstances of the moment.

He was strong, stubborn and determined. But time passes for everyone. On 2 November 1951, the radio broadcast the customary ringing of the Bell of Rovereto, preceded by a short speech by its creator. The priest’s voice was faint, but there and then people thought that this weakness was due to the operations he had undergone a few months earlier. The signs, however, were beginning to be clearer and clearer. On 14 November, the Historical Register of the Bell reported the news of the death of Prince Chigi Albani, Grand Master of the Order of Malta. Then nothing. And that was not normal, especially for a man who had always talked in great detail about what was happening to his creation.

Don Rossaro died on 4 January 1952. The city responded to the news with shows of affection. The priest was considered to be what Giuseppe Parini in La caduta defined as the Good Citizen who 'at the point / where nature and the first / events ordained, guides his intellect in such a way that he esteems his homeland": the one who "directs his intellect toward the goal to which his nature and the early events of his life have led him, so that his homeland may appreciate him.’

In those decades he had commissioned a wealth of statues, plaques and busts for the city of Rovereto. Characters and episodes that were not to be forgotten, especially by the citizens of the city he considered a 'small homeland', built on pride and a shared sense of responsibility.

But while everything started from that territory, the idea of the Bell has projected the city and its inhabitants beyond the boundaries of the municipality. The Bell of the Fallen is the symbol of a vision of reality that led Don Rossaro to explore the world, laying the foundations for work aimed at fostering dialogue between different groups, sometimes even between enemies, with the sole and ultimate goal of Peace. This is, perhaps, his greatest legacy.