THE HISTORY OF THE BELL IN A VOLUME BY MAURO MARCANTONI AND ALICE SALAVOLTI

One hundred years after the first tolling of Maria Dolens, the Campana dei Caduti Foundation sought to critically reflect—without rhetoric—on the century that has passed since October 4, 1925, the date marking the beginning of a story that continues to this day. The task was entrusted to two historians, Mauro Marcantoni and Alice Salavolti, authors of the book Rintocchi di Pace. Cento anni della Campana dei Caduti di Rovereto (Chimes of Peace. One hundred years of the Bell of the Fallen in Rovereto), thanks to which one can relive the adventure sparked by an intuition of Don Antonio Rossaro: casting the cannons of the Great War to make a symbol of Peace. The authors have chosen, among other things, to emphasise the events that led to the current arrangement of the Bell, the relationship with the city and the province, and the international role that Maria Dolens has earned over the decades. We are pleased to preview some excerpts from the volume in these pages.

1. Spaces, symbols, identity

The long avenue, poised between earth and sky, leads to the large open-air amphitheatre that seems to overlook a void, allowing one's gaze to embrace the entire Vallagarina area. Suspended in the middle between two white concrete pillars, Maria Dolens surprises the visitor—not only for its grandeur and the weight of its history but because here, one truly gets the impression that the many evocative and symbolic references—the interweaving of history and geography, collective memories, and the depths of individual consciousness—find their sole centre of gravity in the Bell itself. The direction in which we find ourselves contemplating the area reserved for the Bell is the east-west axis, which, in addition to referencing the sun's daily arc, is the historical orientation of sacred places. Until the early Middle Ages, in fact, Christian churches were built with the apse facing east, so that the priest and the faithful could pray facing the sunrise, an ancient symbol of rebirth adopted by the Christian religion as a metaphor for the resurrection of Christ. But this was also the axis, longitudinal to the Alpine arc, along which the front line ran during the First World War. Vallagarina, located in what was the southernmost part of the Italian Tyrol, was the scene of many bloody clashes and battles. The urban development of the following decades—particularly in the late 20th century—covered, camouflaged, and sometimes obliterated many traces of that past. Yet, despite these erasures over time, artifacts, forts, and trenches still resurface. From up here, the view looks over a panorama that was sadly familiar from the war bulletins of one hundred years ago. The Pasubio massif is dotted with structures, tunnels, and pathways. On Monte Zugna, the remains of a military hospital and the Italian 'trincerone' can be visited. Artillery emplacements and military roads are scattered on Mount Altissimo, Doss Casina, Malga Zures, the Vignola and Corno della Paura.

The direction in which we find ourselves contemplating the area reserved for the Bell is the historical orientation of sacred places

2. An exemplary context of Peace

When Maria Dolens tolls its hundred solemn chimes each evening, the austere and profound call echoes across a valley where the visual elements—the Adige River, the winding roads, and the urban clusters—stretch in the opposite direction, running north to south. This axis links Mitteleuropa and the Mediterranean—regions that, though only glimpsed from here, have always permeated this natural "hinge" nestled within the Alps. Together with neighbouring South Tyrol, Trentino is a borderland. A land that has always sought harmony, not conflict, among different histories, cultures, languages, and interests. An idea of a border not reduced to a sharp demarcation—a wall, barbed wire, or an irreconcilable difference—but its opposite: as proximity, a sense of closeness, sharing not a barrier but a threshold. The one who lives next door is a neighbour, not the enemy. A clear example of this commendable attitude can be seen in the lands south of the Brenner, as well as in neighbouring Tyrol, even in recent times. One need only think of Austria's signing of the Dispute Settlement , which in 1992 successfully resolved the thirty-year-long UN dispute over the South Tyrol issue. An extremely bitter and bloody ethnic-linguistic conflict, which, at the beginning of the second half of the last century, seemed irresolvable, was peacefully ended with the Settlement. This extraordinary achievement, unique in its kind in Europe, saw the participation of numerous figures, both local (South Tyroleans, Italians from Bolzano, Trentino, and Tyrol) and national (high-ranking representatives from the Italian and Austrian governments). A collective effort driven by positive intentions clearly showing that, with the right conditions and intentions, even what initially seems impossible to resolve can be overcome. A coherent and reassuring framework for understanding the border not only as a threshold, a fertile ground for exchange, a permeable passage, but also as a goal—a target of peaceful coexistence to be pursued, achieved, and maintained.

A land that has always sought harmony among different histories, cultures, languages, and interests.

3. Meaning and significance of a symbol

The border as "proximity" rather than division was, in the end, the essence of Don Antonio Rossaro's vision. In the aftermath of the terrible tragedy of the First World War, the priest pursued the dream of building a large Bell, one of the largest ever seen in the world, cast from the bronze of the cannons of the nations involved in the conflict, whose echoing chimes would radiate the message of Peace, commemorating the victims. The voice of the Bell would have united what the howitzers and bombs had divided, sowing death and destruction. In the 1920s, re-emerging from the destruction of the First World War, Don Rossaro's fellow countrymen were driven by the same sentiment shared by all Italians, and by all those in the world who had survived that tragic madness: to move forward, look to the future, and even to forget. There was a sense that every word, every gesture, every action risked diminishing the immense significance of that experience. Until someone takes it upon themselves, in their own consciousness, to embrace the unspeakable, to truly engage with it, and to explore its inherent potential: the potential to bring about change. This is what we might call the 'subversive force of memory'. Not a painful, introspective retreat into the past, but its reinterpretation to guide the future in a different direction. Sometimes, it takes dreamers or visionaries to arrive at this awareness. Don Rossaro's project took that visionary path: to transform the unspeakable into a generative symbol (the Bell, in fact), capable of inspiring a transformation in consciences. The authority, as well as the symbolic and metaphorical presence of Maria Dolens, thus lies in the profound connection between the symbol and the concept it represents. That is, between the physical substance, consisting of an imposing material presence and a majestic sound (the symbol as "the acoustic image," to use the definition by linguist Ferdinand de Saussure, which fits particularly well in this context), and the profound concept of Peace and brotherhood, first envisioned by Rossaro and later renewed and updated by the Foundation in the decades that followed. The inseparable connection between symbol and concept became tangible, infused with meaning, also in its material transformation: from cannon to Bell, from artillery shell to chime.

The voice of the Bell would have united what the howitzers and bombs had divided, sowing death and destruction

4. A message to the world from Miravalle

The Bell would perhaps not have had the symbolic power it has today had it not been for the intuition in 1965 - which at the time sparked heated debates - to place it on the Miravalle Hill on the slopes of Mount Zugna. The place, which at the time did not yet bear this name but was identified as part of the Val Scodella, was in fact devoid of significant features other than its fortunate geographic location. This includes both the wide panoramic view that spans the valley and its proximity to the Military Shrine of Castel Dante, inaugurated in 1938. This monumental structure houses the remains of the soldiers who fell in the First World War, recovered from the area between the Pasubio and Lake Garda. Although just a few kilometres from the centre of Rovereto, over the past sixty years the hill has developed its own identity, deeply connected to the soul of the Bell and the voice of those who have been able to echo its message of peace—namely, the Foundation. This presence has profoundly changed the identity of the environment, giving rise to a unique, distinctive ecosystem. While geographically and legally part of the municipality of Rovereto, it is primarily and foremost under the complete sovereignty of the Bell and the philosophy that accompanies its presence, to the point where one can almost feel an air of extraterritoriality. Here, a place that was once simply a pleasant hill, comparable to many others, has gained glory and significance from its sole dedication to the Bell. It has become the focal point of a complex of symbols and works that evoke a sense of the 'sacred' in the visitor, characteristic of religious shrines, but also reminiscent of the ossuaries and reliquaries of other wars or disasters, across all latitudes. The dedication of the Bell to Maria Dolens - which Don Rossaro, as a priest and believer, clearly intended as a direct tribute to the Mother of Christ – does not, however, disrupt the clear secular nature of the space. It is as if, when speaking here about Peace and recalling the wars of the world, one immediately realises that 'sacred' is not merely religious, but rather spiritual – the deepest human emotion that draws from suffering and the shared awareness of death, ultimately leading to ideals of Peace and hope for a better world. A supranational emblem, transcending all religious beliefs and political ideals, as Don Rossaro himself clearly expressed: "The monumental Bell of the Fallen in Rovereto was consecrated—and will remain so—exclusively in memory of all those who fell in the World War, regardless of their faith or nationality. [...] I specifically wanted everything related to the Bell of the Fallen to be above and beyond any political or nationalistic conflict. In fact, I excluded all military uniforms and national insignia from the Bell's decoration. This way, the Miravalle Hill, with its architectural and spatial layout centred around the Bell, becomes a place where people from all over the world can experience a sense of unity.

A complex of symbols capable of generating in the visitor a sense of the 'sacred' characteristic of religious shrines

The area around the Bell is dotted with signs and symbols. Universal signs and symbols that speak to everyone. Thus, the fluttering flags of countries from around the world lining the entrance drive remind us that the Miravalle Hill is not just one of many shrines dedicated to the memory of wars, but an ongoing, living project. The raising of each new flag takes place in a ceremony that brings together the highest officials of that country, in what might seem, at first glance, like a periphery of Europe, but which, in many ways—culturally, historically, and even economically today—is its beating heart. Not only does each country leave its flag here, but through this symbolic act, it identifies itself with and upholds the principles embodied by the Bell, committing to national peacekeeping and international dialogue. A total of one hundred and six flags surround the Bell, in the amphitheatre of Piazza delle Genti and along the avenue it looks on to: those of the nations, and those of international organisations and peoples: UN, COE, European Union, Red Cross and Red Crescent, Sovereign Order of Malta, Roma-Sinti, Palestinian Autonomous Territories.

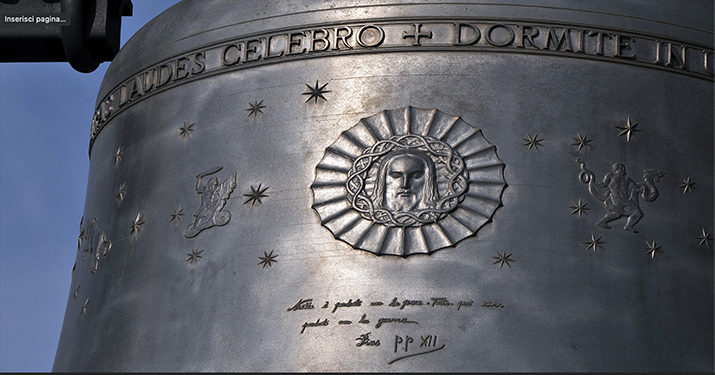

Bas-relief frieze by sculptor Stefano Zuech. Detail of the Ecce Homo and the phrase spoken by Pope Pius XII on the eve of the Second World War.

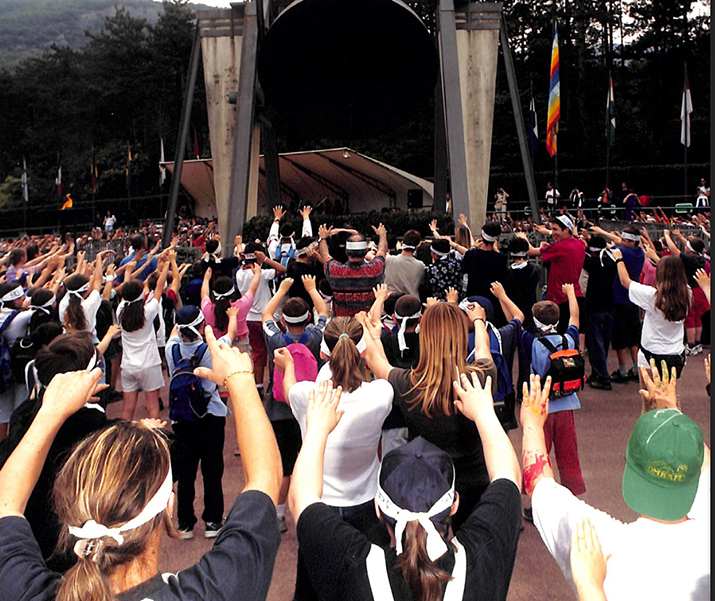

Bas-relief frieze by sculptor Stefano Zuech. Detail of the Ecce Homo and the phrase spoken by Pope Pius XII on the eve of the Second World War. 7th Youth Congress at the Bell of the Fallen, 9 May 2003

7th Youth Congress at the Bell of the Fallen, 9 May 2003 Visit of Nobel laureate Shirin Ebadi, 26 May 2017

Visit of Nobel laureate Shirin Ebadi, 26 May 2017