THE ‘UNREDEEMED LANDS’ ONE HUNDRED YEARS AFTER THE ‘MARCH ON ROME’

INTERVIEW WITH THE HISTORIAN MICHELE CANONICA

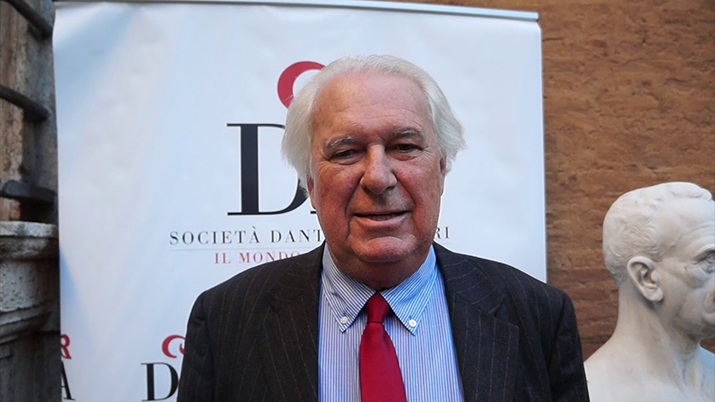

Sometimes it's mainly a question of volume. Saying the same things in a different tone can make all the difference, because there is a dialectical link between quantity and quality. This was explained by Michele Canonica, historian, columnist and president of the Rome committee of the Dante Alighieri Society, after having been head of the Paris committee for some time. The occasion was the conference held on April 8 at the Rovereto Peace Bell and focused on the theme «1922-2022. The "unredeemed lands" one hundred years after the ‘March on Rome’».

It is a touchy subject, as with all topics in history that concern a not-too-distant period, and sometimes, even what is happening in the present day. It all started with romanticism, when «the idea of attributing a collective psychology to a population leads to the political will to unify territories that refer to a specific culture in the same nation». This, says Canonica, who after the meeting answered a series of questions, «occurred in Italy, and beyond, at the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Irredentism was in fact one of the assets flaunted by the Liberals before the First World War. For statesmen of Risorgimento extraction, the conflict represented an effective tool with which to conquer the territories that were not yet part of the ‘Nation’». /p>

With romanticism, the idea of attributing a collective psychology to a population leads to the desire to unify places that refer to the same values in the same nation

But how does fascism fit into this perspective?

By riding on the discontent from the so-called "mutilated victory", that is, the failure to meet the territorial requests of Rome. Many Italians were exasperated because they saw ex-combatants mistreated and would have liked more respect for the effort made to win the First World War after the disaster in Caporetto. There is a conjunction of various factors that stoke the fire of fascist propaganda, and many firmly believed that Mussolini could have conquered territories linked to Italy on a cultural level and even outside the borders. Thus, an environment was created which was favourable to the affirmation of the dictatorship.

If this is the point of contact between Risorgimento irredentism and fascism, what are the main differences?

The fascists insert a degree of anger, violence and propaganda rhetoric that never existed in the cautious figures of Italian liberal politics. The level of "volume" also led to a qualitative difference in action. But everything was based on the fascist promise to maintain stability, also because the Bolshevik revolution had aroused many fears. Mussolini seemed to have a pragmatically operative program, even though in the years of the dictatorship he did not achieve great results in expanding the Italian presence in Europe and devoted himself to colonial conquests. But at the time of the ‘March on Rome’ he seemed like a man who had the ability to actively intervene with a resolute tone and way of presenting himself that appealed to the average Italian. Also, for this reason, the decision of Vittorio Emanuele III not to proclaim a state of siege in the face of fascist provocations, opening the way for the regime, was received positively by the population.

Can irredentism be considered a perspective from which to look at Italian history?

Perhaps this is a bit too much, but it was certainly an important component, especially in Trentino and Alto Adige, where tensions have significantly dropped in recent decades. Many see a model of collaboration in these areas between populations of different languages, cultures and sensibilities.

There is no doubt that between Trentino and Alto Adige there are differences in terms of collective psychology, but they are differences that have found a relatively harmonious conciliation.

How can this perspective help us understand the present?

The deep feelings of a population must always be taken into consideration.

Even when we don't share them. If we look at the war in Ukraine, for example, we are faced with two communities that have a different perception of themselves.

The fascists pursued shared objectives by inserting a degree of violence that had never existed in the proponents of liberal politics

Ukrainians claim a difference from which derives a request for autonomy while the Russian regime makes claims on its neighbouring country, considering Kiev a piece of the so-called Great Russia. In some ways it is irredentism: "We do not want Westerners with the help of NATO and the EU to occupy a land that is ours and therefore we have not waged a war, but a special military operation", they argue in Moscow. It is not a question of sharing, but rather of understanding what is happening in order to find a way to overcome the crisis.

A historical geographical map of Italy