If politics decides what is art

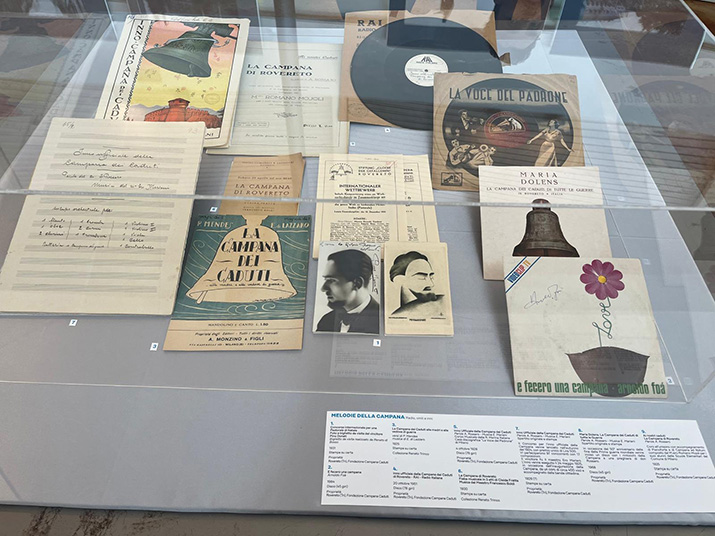

On 12 April, the exhibition 'The Myth of the Bell - One Hundred Years of Maria Dolens', curated by Chiara Moser, was inaugurated at the Foundation's headquarters, celebrating the long and fascinating journey of Maria Dolens. During the opening ceremony of the exhibition, which closes on 31 October, Member of the European Parliament Herbert Dorfmann gave a speech, summarised below.

The 100th anniversary of the Campana dei Caduti is an important anniversary, a 'milestone birthday'. For a century, this Bell has rung every day in memory of the fallen soldiers of all wars. It was commissioned and made in 1925, no doubt inspired by the devastating experience of the First World War. It was here, in this territory that once marked the border between the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the Kingdom of Italy, that the cruel and bloody Dolomite front developed, the scene of an unprecedented human drama.

Not surprisingly, not far from here, the first shot of the war between Austria and Italy was fired in 1915. Yet, those who devised this Bell could not have imagined that the worst was yet to come: the collapse of the world order, the horrors of the Second World War, which would also affect these lands. But the Bell also endured through the long period of peace that followed, and which, fortunately, still accompanies us today.

Today, those wars seem far away. Few of us have personal memories of the conflicts, and probably none of us personally knew their fallen. Peace has become almost a 'logical' condition in Europe, and perhaps because of this we tend to value it less than it deserves.

The second half of the 20th century saw the birth of international bodies such as the UN and the Council of Europe - places of dialogue and mediation - and above all the European Union, which would not have existed without the tragic lessons of the Second World War. We are also in a land that was the birthplace of one of the great founding fathers of Europe: Alcide De Gasperi. He understood that only collaboration between the peoples of Europe could guarantee lasting Peace on our continent.

So does all this mean that we can sleep soundly? That today we are only celebrating a memory of the past? Unfortunately not. For three years now, war has returned to Europe. Aggression has returned, and it has brought new casualties with it. At the gates of the European Union, young people with lives full of dreams and plans are forced to fight and die on the battlefields of Ukraine. Victims of an aggressive, unnecessary and also deeply irrational expansion plan, aimed only at consolidating power at the expense of the common good.

We believed that the world order, based on friendship between peoples, transatlantic cooperation and globalisation in the sense of shared prosperity, was now stable and irreversible. But this is not the case. Selfishness and nationalism are returning. Even in countries that, for a century, have been symbols of democracy, such as the United States of America.

We must remain vigilant. A policy that focuses solely on itself, abandoning international cooperation and democratic values—such as equality, respect for minorities, and individual freedom—is a dangerous one.

Here today we are opening an art exhibition. But when politics takes it upon itself to decide what is art and what is not, what is beautiful and what is not, then we must be concerned. The abandonment of the common good, the exaltation of the nation as an end in itself, a ruling class devoid of culture and the most elementary principles of humanity and respect: all this has already led us to the catastrophes of the last century, catastrophes that this very Bell reminds us of every day.

And these signs are returning, in our own countries too, even in Europe. Sometimes, even in the European Parliament, I am surprised to see just how often today we talk about war rather than Peace. But the European Union is, and remains, a Peace project.

Peace is its greatest success. And every political decision should be taken in the light of this fundamental mission, as the founding fathers envisioned it.

I do not want to be misunderstood: I am not a naive pacifist. I understand that defence is important, and so did Alcide De Gasperi, who already proposed a common European defence. But defence, ultimately, must also have Peace as its goal, in Europe and in the world.

It is therefore a good thing that this Bell continues to ring every day, and reminds us that Peace, democracy, humanity and cooperation are not conquests to be taken for granted, but values to be constantly protected. With these values, this land has become wonderful: a place where everyone can live freely, according to their own dreams and plans. Without these values, we risk that the list of the Fallen not only fades as a historical memory, but a list destined to grow longer.

That is why, on the occasion of the centenary of the Campana dei Caduti, I want to express a sincere wish: that this Bell will continue to ring for at least another hundred years, in memory of the Fallen, and that every day it rings will be a day of Peace, freedom and progress for this land of ours.

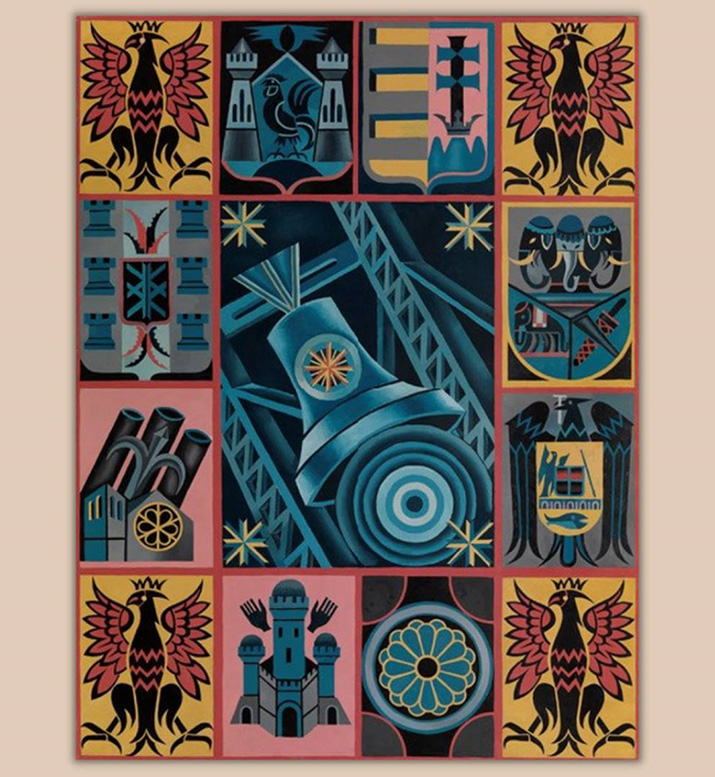

Fortunato Depero, Boundless Generosity (1957)