FOR WHOM THE BELL TOLLS - PART 12

The fate of the Bell was not to ring until the end of World War II, but Don Rossaro did not know this. On the contrary, like everyone else, he thought that the conflict would be brief and that the victory of the Axis was certain—indeed, inevitable. The attention was focused elsewhere. For example, on solving the usual practical issues, such as finding ferrous material to build a stable support on which to place Maria Dolens. Cement and sand were also needed, and not easy to find in wartime. Funding then had to be applied for directly in Rome. This was accompanied by contradictory messages from the priest, who, in a letter to Mussolini, boldly referred to the Bell as 'the exaltation of the heroism of war.'

The distortion is evident and can be attributed to the desire to obtain the promised aid. The request was also directly supported by the prefect of Trento, Italo Foschi, who personally went to the capital to ask for financial assistance.

The funds arrived, along with the growing realisation that the blitzkrieg was turning into a tragedy of enormous proportions. Fascism was slowly waning, and the Director noted in the minutes of January 29, 1943, that 'in light of the bloody drama of the current war, which is erupting everywhere with far more terrifying proportions than the 1914-1918 World War, and so that so many heroes may receive worthy and lasting commemoration, serving as a perennial and salutary reminder of the "human beasts," he proposes that the Noble Bell of the Fallen, while remaining a memorial to the fallen of the World War, extend its noble mission to include the Fallen of the current war and indeed all future wars, henceforth to be called the "Bell of the Fallen in War.” Article 1 of the Magna Carta will be changed to reflect this'.

Things were changing rapidly. After the fall of fascism on 25 July 1943, signs of unrest began to appear throughout Trentino. The supporters of the regime were deflecting. "In the factories," notes Don Rossaro in his Diary, "the 'leaders’, who were once tyrants under the cloak of fascism, are now gentle, kind, and they are claiming to be anti-fascists! Cowards!" Intellectuals sought self-exculpatory formulas to justify their adherence to the regime, or urged others to view future problems as if fascism had been a 'parenthesis,' according to Benedetto Croce's definition.

Meanwhile, the Allies arrived. On 2 September 1943, shortly after midday, two squadrons of British aircraft flew over Rovereto. A few minutes later, the first bombs fell in Trento. On the 9th, the day after the armistice, it was Rovereto's turn.

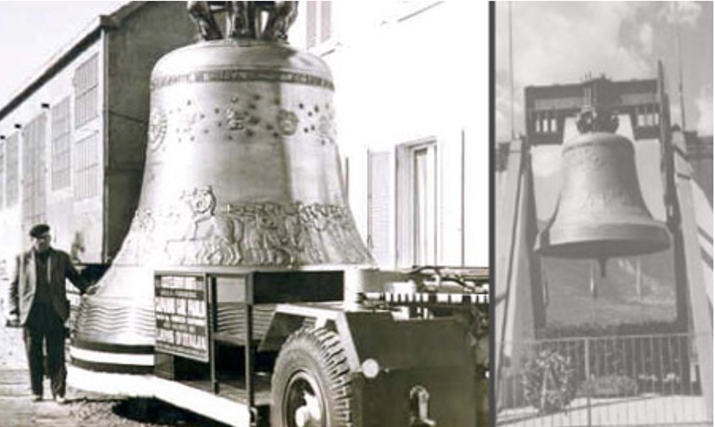

During the six hundred days of the German occupation, as we read in the Historical Record, work was completed on the plinth and the final fixing of the Bell on the iron support. It was 5 May 1944, everything was in place, but not safe. On 17 November 1944, German officers had a conversation with Don Rossaro, announcing that the Bell could be requisitioned to be melted down to make cannons for the war effort. A kind of return to the starting point, a mocking vicious circle of the madness of war. From cannons to Bell, from Bell to cannons.

The priest did everything possible to prevent this. To close this potential loophole, it was decided that the bell would henceforth be rung 'for all the fallen in present and future wars. (...) Since today's war has brought its front lines beyond the battlefield and into towns and villages,' the Director proposed that the bell should ‘also commemorate the civilian fallen who perished in the bombings, thus dedicating 'November 2nd annually in perpetuity to their memory’.

The conflict was coming to an end, the occupation was nearly over. Don Rossaro describes the Germans' flight northwards with a certain compassionate tone, comparing it to that of 4 November 1918. But before leaving, the occupying troops wanted to pay tribute to their dead. On the morning of 3 May 1945, the priest was ordered to ring the bell to honour the German dead. Don Rossaro held back until the occupiers, compelled by the unfolding events, abandoned the city. Again, Maria Dolens remained silent, and did not even sound when the British arrived.

The war was not yet over; it was necessary to wait for the first light of 4 May, when the American troops entered the city. The crowd invaded the streets and invariably a call was launched for the Bell to be rung. Don Rossaro agreed, but this wasn’t the right time either.

Everything was in place, but the American commander raised a security issue, he feared that the people gathered in the square would pose a serious danger. Nothing came of it. The priest's comment was definitive: "It is fate that the Bell must ring in Peace! ... Once again: everything has gone haywire. There was not even time to warn the citizens. At 8 p.m. large crowds had formed in the Piazza. Suddenly and unexpectedly, the numerous and skilled military band of the Czechoslovakians arrived, travelling from Trento to Riva. Our good friend Major Stockar managed - to put on an impromptu performance - to keep it in Rovereto to celebrate the Bell being rung for the very first time. Everyone was hugely disappointed and disgruntled! ... The band stopped anyway: in homage to the Bell, it played a highly acclaimed concert featuring the Czechoslovak anthem, amid a festive display of fireworks. That was the first solemn tribute to the Bell'.

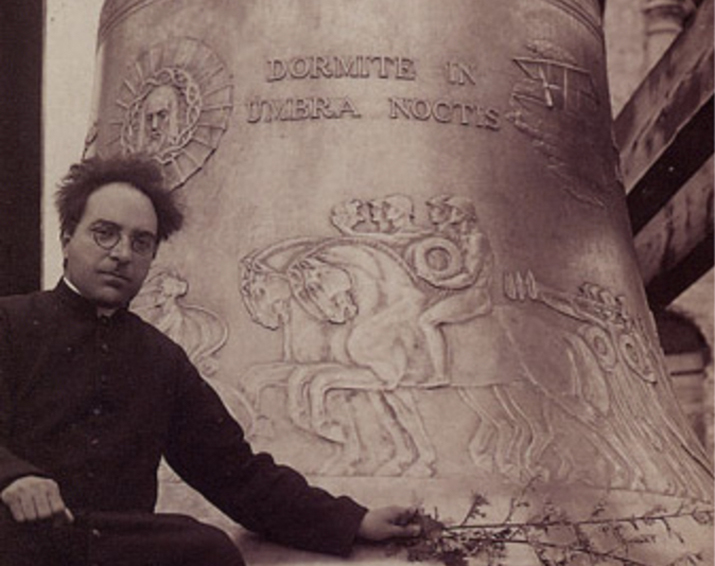

Don Rossaro and 'his' Bell