FOR WHOM THE BELL TOLLS - P20

THE DIRECTORSHIP OF PIETRO MONTI

When Pietro Monti was called to lead the Campana dei Caduti Foundation in February 1984, the institution found itself at a pivotal fork in the road. A lengthy legal dispute with the War Museum had slowed down its activities, leaving the Colle di Miravalle in a state of uncertainty—halfway between memory and oblivion. With Monti, the third Director in its history after Don Antonio Rossaro and Father Eusebio Iori, the Bell found a new direction: it was no longer merely a custodian of memory, but became a workshop for dialogue and reflection on contemporary conflicts.

The task was far from simple. The institution carried sixty years of layered history on its back. Founded in 1924 as a symbol against war, it had faced the risk of being absorbed into the nationalist rhetoric during the Fascist period. However, later, under Father Iori, the Bell embraced an international outlook with the creation of the Piazzale delle Genti. Monti inherited a valuable, though sometimes burdensome, legacy. His twofold mission was clear: to make the Bell’s message increasingly relevant without betraying its roots, and to equip the institution with practical tools to accommodate its growing visitor flow.

The first major turning point came in September 1984, just months after his appointment, with the “Riflessioni sulla Pace” (Reflections on Peace) conference. After years of limited activity, the Foundation once again emerged as a promoter of high-profile cultural initiatives of considerable international relevance. The discussions highlighted a crucial insight: every era interprets its symbols differently. The Bell, born as a warning against war, could now serve as a platform for human rights—a place where the younger generations could be educated and meet. Monti recognised that symbols hold immense significance at the moment of their creation, but must also resonate with people across other generations; otherwise, they lose their deepest meaning: "Peace is always Peace, but Peace, war, or human rights change over time—not in their essence, but in how people perceive and experience them". Thus, unless they are renewed, even the most powerful symbols risk losing their impact.

This perspective led to one of the most significant projects of Monti’s directorship: the International University of Peace Institutions (Unip), launched in the early 1990s. With support from the Province and in collaboration with the University of Trento, Unip brought an international scientific committee and practitioners from dozens of countries to Rovereto. It was not a university in the traditional academic sense, but a space where those working on the frontlines of peace initiatives could receive training and exchange ideas and skills. The topics addressed ranged from social conflicts in Brazil and the Balkan wars to the role of the media, globalisation, and indigenous peoples’ rights.

The impact was substantial. Through Unip, the Bell positioned itself on an international map extending far beyond the memory of the First World War. A few tensions did arise, however. Certain local groups sought a greater “return” of activities to the region, fearing it might be overshadowed by the initiative’s international focus.

Monti, however, saw the presence of people from thirty countries in Rovereto as a valuable asset for the community, even if its benefits were not immediately measurable. This tension between local and global perspectives accompanied Unip’s trajectory throughout.

Alongside education, the Foundation promoted research and information. This led to the creation of the Balkans Observatory, a response to requests from NGOs operating in the former Yugoslavia. The centre became a reference point for monitoring projects, assessing their effectiveness, and collecting data in a crucial European region during the 1990s. The Bell thus evolved into a hub of a civil network actively engaged in crisis zones.

Yet Monti’s vision extended further. Another key area of engagement was interreligious dialogue. Thanks to the efforts of Vice Director Don Silvio Franch, the sixth World Assembly of the World Conference of Religion and Peace was held in 1994—first with an audience with the Pope in Rome, then with sessions in Riva del Garda, where representatives from religions around the globe gathered. It was a moment of worldwide significance, supported logistically by the Foundation, with a crowd of believers praying at the foot of the Bell. "I would say it was a great event,” Monti reflected, noting that he was unsure “to what extent the people of Trentino grasped its importance, also because the local press was not very responsive or engaged; but in my view having the Patriarch of Constantinople and other prominent religious leaders in Riva del Garda was something truly extraordinary for the society of Trentino”. "I believe it is difficult to measure the practical results of such initiatives here too," he continued, adding that “coming together, talking, and praying together serves a purpose. Understanding whether this goes as far as to influence moments of conflict is much harder”.

Monti’s directorship also left a mark in tangible ways, such as transforming Miravalle into an open, welcoming space. In 1986, the International Year of Peace, a concert by Miriam Makeba opened new perspectives: the Bell became a place of culture and dialogue through music. In subsequent years, events dedicated to Africa, featuring international artists and local groups, showed that the memory of war could coexist with new forms of dialogue and solidarity.

After nearly two decades of tireless commitment, Monti concluded his directorship, leaving behind a Foundation profoundly transformed. It was more organisationally robust, thanks in part to institutional support, and it was recognised as an institution capable of addressing major peace issues on a global scale. The legacy of his regency was not merely preserving the Campana, but guiding it beyond the memory of war into the complexities of the present.

His vision had been clear: symbols only stand the test of time if they speak to people across generations. Under his leadership, the Campana dei Caduti learned to speak not only to war veterans, but also to NGO workers worldwide, Peace mediators in the Balkans, religious leaders of all faiths, and young people confronting globalisation both as a challenge and an opportunity.

Since then, the daily tolling of the Bell has served not only as a reminder of the past, but also as an invitation to reflect on the present through the lenses of rights, dialogue, and coexistence among peoples.

Visit of the Dalai Lama (from left: Rovereto councillor Donata Loss, the Dalai Lama, and Director Pietro Monti)

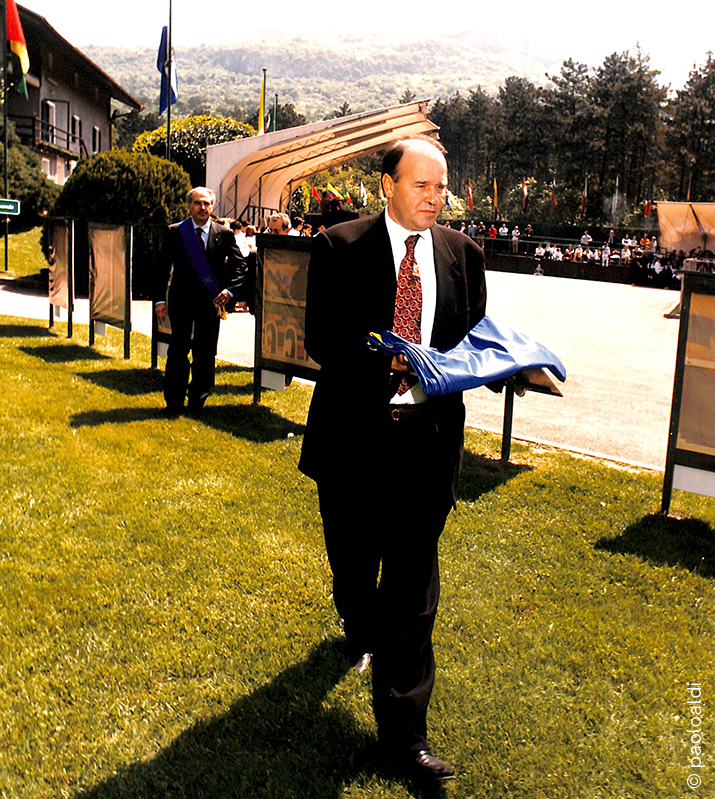

The Director Pietro Monti at the Ceremony for Europe Day

Visit of the President of the Republic Carlo Azeglio Ciampi on the occasion of the Ceremony for the 75th Anniversary of the first tolling of Maria Dolens (from left, the Regent, Pietro Monti, the President of the Republic, Carlo Azeglio Ciampi, behind them the then Minister of Defense, Sergio Mattarella)

Assembly of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe joins the Foundation (from left: President of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe Lord Russell-Johnston and Director Pietro Monti)