Afterwards, once everything was accomplished, it all seemed natural, almost taken for granted. Yet beforehand, no one had even considered it. This little publication is about how ideas become reality. The creativity, commitment and effort needed to convince everyone, the difficulties one encounters, the mistakes one makes and the satisfaction of hearing the Bell of the Fallen ring for the first time. But it doesn’t end there because from that moment on the story that leads to us begins — to the Maria Dolens we know today, to its relations with the United Nations and the Council of Europe, to the long line of Presidents, to the passion of those who work there every day, to the wonder of visitors hearing for the first time the emotional power of its chimes, and to the ‘Avenue of Flags’, continually enriched by the banner of yet another nation that believes in this mission — a nation taking one more step towards Peace, because there is no alternative to dialogue.

The first tolling of the world's largest Bell was heard on 4 October 1925. It could all have stopped on that day and this would already have been a great story. Yet it is important to understand what that event meant for the decades that followed — to determine whether the vision of a provincial priest who, in the aftermath of the Great War, sought to create a symbol of Peace by melting down cannons once used by opposing armies, remains relevant today. Let’s start from the beginning, from the sunset of 5 May 1921, when Don Antonio Rossaro had the idea. He himself tells how it happened, under the pseudonym Timo del Leno, a fictional character who, on that day, found himself standing under the Arch of Peace in Milan. His tone is emphatic, almost fairy-tale-like, perhaps a little naïve. But we must grant that much, at least, to a visionary.

"It was sunset on 5 May 1921, and he [Timo del Leno] had lingered over a newspaper article describing how, at that very hour, thousands of cannons across France would be fired to mark the centenary of Napoleon’s death. Under the vault of the historic Arch, absorbed in the splendour of that epic, he looked up to see a blazing sunset over the Resegone, and was suddenly struck by the sound of “Ave Maria” coming from a nearby Convent. His heart was at once overwhelmed by a tumult of arms and monastic hymns, torn between two colliding worlds — the world of war and the world of Peace. Far away, the rumbles of the cannon faded into the immensity of the horizon; close by, the ringing of the bell strayed into the mysterious regions of his heart. And the idea of Peace triumphed and rejoiced in the merry flutter of swallows darting beneath the tender reawakening of the stars.

Beyond the imaginative style, wrote historian Armando Vadagnini, “one can perceive the spirit of the period following the end of the conflict: on one hand, the restless memory of those who had survived such a ferocious war; on the other, the deep longing for reconciliation of hearts before the reconciliation of nations through treaties and political compromises. Hence the dream that the priest from Rovereto nurtured day after day: to create a “monument that was not the usual cold allegory cast in bronze or marble, but one that, with a living voice, would resonate and move hearts in honour of so many fallen heroes, of so many victims left without the solace of tears or flowers”.

The Bell, therefore, was born on solid local foundations, creatively interpreting the long history of Trentino and drawing its lifeblood from the spirit of solidarity that has long defined, and still defines, Rovereto. The ethical foundations of the project are, first, to honour the victims of war, and second, to inspire humanity to pursue the paths of Peace as the basis for the renewal of civil life and human progress. Maria Dolens draws its inspiration from the Franciscan spirit: a concrete vision of humanity scarred by the ravages of war, urging a return to cooperation to make Dante’s “flowerbed that makes us so fierce” a more habitable world.

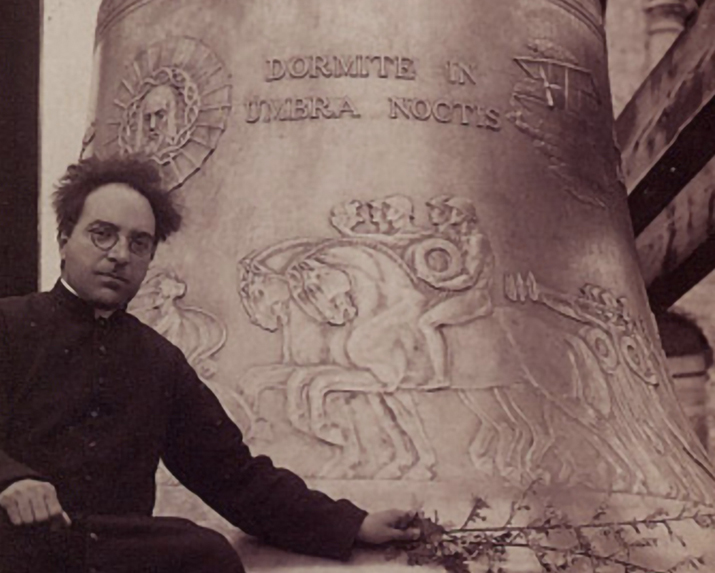

Don Antonio Rossaro with his 'creation'